Is Trump the ultimate personification of the ‘Archimedes Principle’ in leadership which – rather than DEI – is what crumbles competence and shrinks whole organisations?

The little-known leadership ‘Archimedes Principle’ – as well as ‘Failure Demand’ in public services – are two things that all too often wreak havoc through our organisations, the first vertically and the second horizontally. They ripple through our workplaces with destructive domino effects that are widely-recognised by employees.

Yet – like the proverbial ‘six blind men and the elephant’ – we largely lack the clear shared language we need to fully understand – and then remedy – these situations. So our organisations plunge into these downwards spirals over and over, yet this somehow continues to remain hidden… in plain sight.

I also hope here to help you to decide for yourself whether Trump’s new Presidency is currently the illustration par excellence of this leadership ‘Archimedes Principle’ at work. Indeed whether the US has in fact lacked a fully competent President – who consistently makes use of dynamic logic and a 20-year, or more, time-horizon – for all of the 21st century so far: ‘the longest period in US history devoid of a president capable of the office’, as it has been described.

Trump’s surely in for quite a shock should he ever wake up to the realisation that he himself may be the biggest danger to complex systems (like air traffic control), not DEI recruitment, as he likes to proclaim.

Is the simple explanation for Trump’s behaviour and impacts that it is the downward leadership ‘Archimedes Principle’ in action? You decide…

‘Failure demand’: the hidden wasteful activities that quietly colonise public service organisations

Before we unwrap Trump and the impact of the leadership ‘Archimedes Principle’ in organisations, we’ll take a quick detour as I more briefly describe the second crucial and damaging domino effect I’ve mentioned: ‘Failure Demand’. Some of you will have heard of it before.

There are even the first flickerings of a wider recognition of its importance: the Guardian recently had an article titled ‘Proper care for people who are struggling isn’t ‘soft’ – it saves cash’, which was essentially about ‘Failure Demand’, though without actually naming it.

To understand what Failure Demand is, it helps to first understand ‘value demand’: ie what we want from a public service. For example ‘I’ve been made homeless and want a roof over my head’, ‘I want a timely GP appointment’ and so on.

By contrast, Failure Demand is the “demand caused by a failure to do something or do something right for the customer” writes John Seddon, who first coined the term.

A study of UK primary care gives some examples of Failure Demand: “In a healthcare context, failure demand might appear in many forms, ranging from unnecessary prescriptions or repeated diagnostic tests, to repeat patient presentation owing to failure to treat a condition at first contact. Other activities, such as unnecessary follow-up visits, might also be classed as failure demand”.

At a deeper and more pervasive level, entire standardised services often operate as impersonal pathways in silos. They seek efficiency “by buttoning down processes, protocols, pathways, eligibility criteria etc” (as Mark A. Smith puts it) – but ultimately can end up understanding the actual person less and less, and so can often gradually build up more and more unresolved issues: Failure Demand.

Focus on flow and costs will fall, focus on costs and costs will rise

- John Seddon

Work that should have been dealt with, problems that should have been solved, end up returning unresolved back into the system as further work. Unhelpful targets are a particularly common cause of Failure Demand, as are things like call centres, that supposedly represent an ‘efficient’ solution but often explode the levels of Failure Demand. As John Seddon points out, there is a paradox here: focus on flow and costs will fall, focus on costs and costs will rise.

Seddon has found that ‘failure demand’ can account for anything between 20 and 60 per cent of all customer demand, in financial services. In local authorities and police it can be up to 80 or 90 per cent. It’s a similar story in healthcare.

Turning off Failure Demand has an immediate positive impact on the capacity of the system.

Yet when organisations get in the public eye by publicising their figures for the ‘rising demand’ on their services, they never break out the differing proportions of value demand and Failure Demand. In many cases real demand may well not even in reality be rising at all, whilst the proportion of Failure Demand continues to burgeon without comment.

Brian: the £2m cost of an endless cycle of ‘Failure Demand’

By moving away from standardised pathways and fragmented support, the pioneering Changing Futures team in Gateshead – to give just one example – were able to give people the help they really needed, rather than only what protocols dictated (which too often leave people bouncing around unhelpfully between numerous services).

For example, one alcohol-dependent frequent A&E attendee, Brian, had “had over 3,000 interactions with services in 14 years and yet remained fundamentally misunderstood” (The Liberated Method - Rethinking Public Servives, page 12).

Brian, it turned out, had consumed over £2m of these services (an astonishing total!) – with this costly juggernaut only stopping once the Changing Futures Gateshead team used their ‘high support, high challenge, high connection’ method to shift the needle on the underlying issues that were causing his instability and crises in the first place.

The Government’s Minister responsible for public service reform, Georgia Gould MP, publicly commented that Gateshead’s ‘Liberated Services’ approach had made such a difference to Brian’s life that the local A&E Department soon presumed he must’ve died, when his regular appearances there stopped, once the relational ‘Liberated Services’ approach kicked in, replacing the standard processes and silos that are the normal offer – and had failed to really reveal or resolve Brian’s underlying issues.

Many of us will ourselves have spotted smaller examples of Failure Demand: I know of one NHS 6-week initial assessment target that is way too often pointless and immediately out-of-date, because the actual treatment itself usually won’t start for another 6 months or a year, meaning a second fresh assessment will have to be done anyway prior to its start. In other words two assessments are done (one just to satisfy the imposed target), when only one is needed, soon before the treatment starts.

The £37 billion saving if relational services replace today’s purportedly ‘efficient’ services – and shrink ‘Failure Demand’.

The potential savings if the ‘Liberated Services’ approach became the norm are impressive, to say the least: Prof Toby Lowe recently calculated that the £50k average saving per person (with multiple complex needs) that was found in examples from both Thurrock and Changing Futures Northumbria would translate into a £37 billion saving on the costs of public services, if repeated for every person in the UK with those needs.

This could well even be an underestimate: “These figures do not include any of the savings from prevention of people becoming multiply disadvantaged, nor from the improvements arising from supporting everyone more effectively” (see Human Learning Systems: Radical Pragmatism, p.11).

Just over a decade ago, another report – Saving money by doing the right thing: why ‘local by default’ should replace diseconomies of scale (Locality/Vanguard, 2014) – similarly analysed data on savings from ‘Liberated Services’-style relational approaches, this time largely in Stoke, Redditch and Bromsgrove. It calculated a figure of £22bn (inflation adjusted) in annual savings, the same as the UK’s budget ‘black hole’.

It's far better for the staff too, the Guardian article understandably concludes: “Given a chance, most public sector workers would prefer to end the cycle of procrastination and responsibility-avoidance that characterises much of their day-to-day existence”.

As mentioned, the Government Minister responsible for public service reform, Georgia Gould MP, is very supportive of the ‘Liberated Services’ example in Gateshead (see other case studies round the UK too). Let’s hope the Treasury and No. 10 will soon join her in the Cabinet Office in getting behind these more effective, less costly, relational and strengths-based approaches – and stop wrongly asserting that real reform must always be costly, when it could in reality save many billions.

“Given a chance, most public sector workers would prefer to end the cycle of procrastination and responsibility-avoidance that characterises much of their day-to-day existence”

- Phillip Inman, The Guardian

The ’Archimedes Principle’: how a top leader’s capability level cascades down, shrinking – or growing – the whole organisation

In the same way that Archimedes formulated the principle that water finds its own level, our organisations change their shape and size over time to fit themselves to their Chief Executive or leader’s capability. When a new leader comes in who is less complex, less capable, they will soon end up (unconsciously) shrinking their whole organisation, and what it can achieve.

This isn’t merely some vague metaphor about the effect of incompetent leadership, but is based on – as we will see – a very concrete, empirical measure of whether the leader possesses the cognitive capability for the longest time-horizon tasks on their plate, or not.

Can the leader actually do the heavy-lifting required in their role? In other words, in a highly complex situation, what are the number, the rate of change and the ease of identification of the key factors that are in play?

How far into the future can the ambiguity and complexity of factors be managed and anticipated by a leader? This ability to foresee and expect problems enables them to be avoided. If, on the other hand, a leader lacks sufficient problem-solving capability, it means they aren’t able to cure the difficult problems.

Some other common results of cognitive capability below what’s demanded by the role include:

Unsolved big problems “lurk in dark corners, fester awhile, and then return”

Because they are never fully dismissed they come back – meaning that the leader’s plate piles higher and higher, leaving no room to tackle anything new.

Incompetent top leaders will also tend to appoint other incompetent leaders further down the hierarchy: “this becomes a cascading impact”.

Bad leaders also drive capable people out of an organisation (“as a matter of self-preservation, a capable person will not take instructions from someone less competent and will leave” (nb quotes come from Ken Craddock’s book).

Negative financial results will follow a few years later (as Sandra King Kauanui’s research has revealed).

All these characteristics are illustrative of the ‘Archimedes Principle’ in action: the drip-drip-drip of your organisation shrinking to fit a leader’s capability.

The characteristic of the return of big problems that have not been dealt with feels to me very reminiscent of how unresolved problems in services return into the system as Failure Demand. Though Failure Demand undermines service flow ‘horizontally’ across a system, rather than rippling down ‘vertically’ through the various organisational layers from a Chief Executive, as with the ‘Archimedes Principle’.

‘Surgeons’ who shrink – and ‘Architects’ who grow – their organisations

Sandra King Kauanui’s research confirmed that a CEO’s cognitive capability determines the growth or shrinking of the organisation – though this effect is only seen after three years. (These were family-owned firms, offering a unique natural opportunity to study the varying impacts of big shifts in leader complexity and time-horizon, as these successors chosen from within the family vary more widely than usual in capability for complexity). She suggests using something very similar to the leadership maturity assessment I have suggested for identifying and recruiting transformative ‘Architect’ leaders.

This three-year gap also feels familiar from the study of ‘Architect’ and ‘Surgeon’ leaders in Education shared in my post last year about the pressing need for more participative, ‘Architect’ leaders within the NHS.

Indeed the seven-year study of the impact of different types of Education leaders I shared in that post is very much a case study in how differing leader capability will quietly shrink or grow an organisation.

Unfortunately, it found that the ‘showy’ leaders who get the public plaudits and the high-paying roles were the ones who shrunk their organisations, chasing simplistic targets. And the ‘Architect’ leaders risked getting fired as they “quietly redesign the school and transform the community it serves”. Their positive results would take about three years to come in. It certainly feels like the ‘Architect’ leaders were dealing with multiple factors to grow the school, and using dynamic rather than static logic: “They take a holistic, 360-degree view of the school, its stakeholders, the community it serves, and its role in society”.

“They are visionary, unsung heroes. Stewards, rather than leaders, who are more concerned with the legacy they leave than how things look whilst they’re there”: the mark of leaders who are using a longer time-horizon.

Of the five different types of Education leaders analysed in that research, the ‘Architect’ was the only type that was ‘truly effective’.

Financially, it was also found that even just boosting the number of ‘Architect’ leaders of schools to 50 per cent would “would increase the UK’s schools performance by 9.68%”.

With a second Trump Presidency the search for a first competent President of the early 21st century becomes even more urgent

Let’s move away from more commonplace public service leadership for a while and look to public service writ large, perhaps the most powerful public service leaders in the world: the Presidents of the USA. (Though the parallels and lessons for organisational leadership more generally are pretty self-evident throughout!).

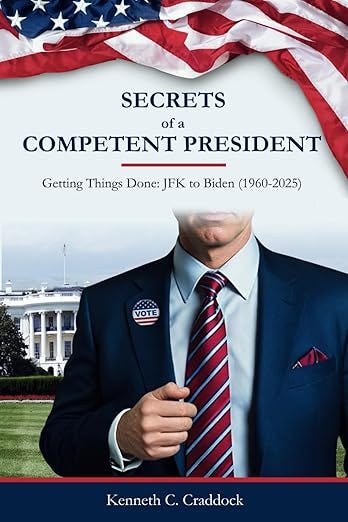

I want to give immediate credit to a rather fabulous and eye-opening recent labour-of love book by Kenneth Craddock: Secrets of a Competent President – Getting things done: JFK to Biden (1960-2025).

It’s what prompted me to write this post, after I suddenly noticed what I believe to be parallels between the two failure domino effects I’m discussing. It’s a very welcome work, not least as it’s unique: a topic I never expected to ever be able to read a whole book about, let alone a series of four.

I love the little-known (to me) historical facts that the book is peppered with too. For instance a past US election where the domination of oligarchs had reached its then apogee, all the way back in 1896. In the post-Civil War period the need for reunion had shrunk the political focus to the local level: “The voters lived through decades of ‘over-fed, undistinguished’ presidents who appealed to Civil War issues. This emphasis contributed to the sense that pressing national issues were not being addressed and they weren’t”.

“The final straw came with the election of 1896. The huge money of Eastern monopolists backed the Republican nominee, William McKinley, while his opponent only received small donations. This signalled the Presidency could be bought. The concentration of money and economic power could be transformed into political power. The ‘age of monopoly’ reached its apex”. Plus ça change…?

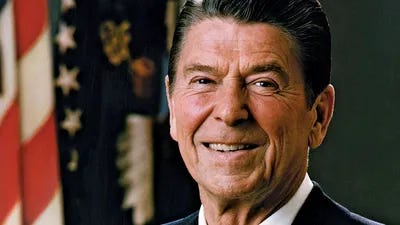

I’d forgotten, if I ever knew, that Reagan had in the 40s been a trade union leader. But when communists “flat-out lied” to him to advance their cause, their “dishonesty enraged him and drove him to the right”. (Not to say the book’s entirely perfect: it has some of the weaknesses self-published books tend to have).

The biggest impact of the book, though, is seeing how its author Ken Craddock has become concerned – very concerned indeed! – at the lack of competent presidents he finds in recent history: “The early 21st century has not produced a competent president. This is a major deficiency and may get worse”, he writes.

“If we do not soon elect a competent president we will not long continue to be considered a first-rate country”, he warns.

To succeed in their hugely challenging role, Craddock argues, a President needs to be able to think (and act) over a 20-year ‘time horizon’ at a minimum. With less than that 20-year minimum, “the major problems would be left undone, kicked down the road to a successor”.

“The influence of presidents using lesser logic levels evaporated almost as soon as they left office”, Craddock’s research found.

Presidential debates reveal cognitive complexity

His book, which runs through to Biden and then Harris vs Trump, is – as mentioned – only the first of four – with the rest of the series going back all the way through the rest of the 47 Presidents in detail, including the four real ‘clunkers’.

Astonishingly – or perhaps it’s so obvious it’s staring us all in the face? – Craddock found that the material that proved so revealing of capability actually came through analysis of US Presidential debates, where candidates traditionally have to think on their feet. This setting clearly reveals the complexity of their thinking (or can do; it’s become a bit murkier in recent times, as we’ll see).

It takes a bit of a mental shift to follow Craddock in trying to focus on the quality, or complexity, of candidates’ thinking, rather than the usual nitty-gritty of their different political positions and proposals, that we’re used to.

For example in the renowned JFK vs Nixon debates (the first televised presidential debates), Nixon used the cumulative logic of lists of points. JFK, on the other hand, was able to use a more complex serial logic to pull his lists into causal linkages.

As well as the JFK-Nixon debates of 1960, the debate between Reagan and Carter in 1980 and between Reagan and Mondale in 1984 made the dynamic capability of one of the two candidates particularly evident to all.

In 1980, for instance, Reagan used dynamic logic whilst Mondale was static.

Higher cognitive capability gives a wider scope for solving problems and viewing the future – and such cognitive differences can cow a rival during a debate.

Indeed, the US public appear to intuitively ‘get’ these cognitive differences between candidates and have historically usually elected the candidate with higher cognitive complexity, argues Alison Brause in her 2000 doctoral dissertation, which Craddock also draws on.

Her research also found an interesting age-related effect: Carter and Ford had equivalent cognitive capability but Carter was a generation younger, and so won. Brause concluded that voters choose not in favour of youth, per se, but in favour of future cognitive growth. In the 2008 Presidential debates Obama and McCain both showed that they could present lists and use Cumulative Logic (ie static thinking) to address issues. But Obama was a generation younger than McCain and won the election.

So, none of this is exactly hidden – voters seem to intuit it, and other politicians often sense who’s up to the job too. Michael Bloomberg, the former Republican Mayor of New York, for example, in 2016 said that only three people had the mental skills to ‘run the railroad’: John Kasich, Jeb Bush and Hillary Clinton. (He didn’t include Trump).

“Historically 100% of dynamic thinkers have been re-elected. And almost all the non-competent ones, who only use one of the static logics, are defeated in their re-election attempts”

As mentioned, to be competent, presidents need to be using one of the two forms of dynamic logic (ie the serial or parallel logics) and to be thinking across at least a 20-year time-horizon. In re-election campaigns, historically 100% of dynamic thinkers have been re-elected. And almost all the non-competent ones, who only use one of the static logics, are defeated in their re-election attempts. (Alongside the competent Presidents there were also, argues Craddock, 23 presidents who were unable to fulfil the position and the four clunkers).

Voters’ perception of nominees actually shifts away from ‘horizontal’ policy issues to ‘vertical’ capability in final 2 weeks of campaigning, adopting “the founders’ perspective”, Craddock finds, “even though most of the horizontal pollsters missed it”.

“The American voters are unlikely to stop now”, he adds.

Recent developments which have weakened the link between candidate capability and electoral success

More recently a number of factors have sometimes weakened Presidential debates in this role of being relatively pure conduits for assessing a candidate’s cognitive complexity.

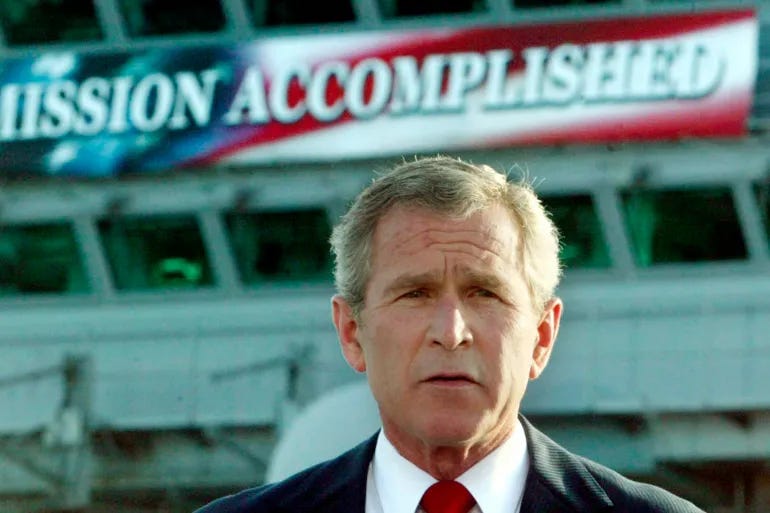

When Karl Rove began his debate coaching of Bush, drilling him in key talking points, he was able to make Bush temporarily appear to be a higher capability leader. When debates revolve around talking points rather than involving logic of any kind, they become just a test of memory and regurgitation of facts – defeating the whole purpose of debating.

This can be spotted, though, ie when a candidate raises one complex point – but then immediately reverts to a disconnected list. This is all exacerbated by journalists who focus on political positions rather than probing the complexity of a candidate’s thinking.

“With Trump,… dominance resembles the ability to solve problems, but isn’t.”

Overall, this means that debates worked well only up to 2000. With Trump, another factor comes into play too: his domineering style is too easily mistaken for the kind of cowing that can happen when a more capable, complex leader debates a less capable leader. In other words, dominance resembles the ability to solve problems, but isn’t.

Static vs Dynamic thinking explained

As mentioned, Craddock explains how research has found that thinking moves through four different types of logic:

1. Static

- A. Declarative (a statement, a directive, not connected to others)

- B. Cumulative (multiple statements together)

2. Dynamic

- C. Serial (sequential cause and effect, if-then)

- D. Parallel (systemic thinking, with multiple paths leading from a cause, then to an effect, which itself becomes a cause)

Evelyn Waugh once wrote it was ‘absurd’ to divide people into sexes when they would be better classed ‘as static and dynamic’

- Kenneth Craddock

Most adults move through these four types of logic applying them to ‘symbols’ and a smaller proportion go on to repeat the use of these logics but now also applying them to ‘abstractions’ (Craddock labels these zones of symbols then abstractions as ‘orders’).

Craddock points out that “Evelyn Waugh once wrote it was ‘absurd’ to divide people into sexes when they would be better classed ‘as static and dynamic’”, quoting from Waugh’s first novel, Decline and Fall.

Trump’s ‘archipelago of dots’ – a static thinker at work?

OK, this mix of logics, orders and time horizons admittedly may well be starting to feel a wee bit over-complicated. To keep things more straightforward, let’s follow Craddock and also alternately just give them a number, a leadership Level.

For example, George Bush was a Level 6 leader (using Cumulative logic with a 10 to 15-year time-horizon).

Clinton had a time horizon of 15 years at the start of his first term, and 20 years before the end of his second, a move from a Level 6 to a Level 7 leader.

Nixon grew to become a Level 7 leader in opposition, and then won the election.

G.W. Bush used static Level 5 logic, with many of his decisions appearing to have a time-horizon of only five years. His Vice-President, Dick Cheney was Level 7, an unusual inversion!

The later Hilary Clinton vs. Bernie Sanders debates used Dynamic logic in a few instances – but it was not sustained. And the 2016 Clinton vs Trump debates showed neither nominee had the capability to handle the complexity needed for an effective presidency.

Obama was a Level 6 leader, and likely grew to Level 7 during the Biden presidency: ‘almost there’ in terms of being a fully competent president, according to Craddock.

More recently, in June 2024 Trump used lists several times, showing he might have grown as a leader, from Level 5 to 6. But in the early days of ‘Trump 2.0’, it’s already clear that that rise was just a blip: he’s now firmly ensconced in Level 5 static thinking, using simple declarative logic.

“In June 2024 Trump used lists several times, showing he might have grown as a leader, from Level 5 to 6. But in the early days of ‘Trump 2.0’, it’s already clear that that rise was just a blip…”

In his Guardian sketch the day after Trump’s inauguration John Smith commented: “After the relative discipline of his inaugural address, Trump was back to the weave, a jumble of disconnected ideas with all the coherence of what John Bolton, his former national security adviser, calls ‘a series of neuron flashes’.”

His thinking appears as ‘an archipelago of dots’ with ‘no constant trajectory’, Bolton put it in his 2020 memoir The Room Where it Happened: A White House Memoir.``

Putin, by contrast, is a Level 8 leader – who plays “three-dimensional chess”, as the former Trump Secretary of State Rex Tillerson put it. (Tillerson would himself have been a Level 7 or 8 leader, to survive as CEO of ExxonMobil. He found Trump too mercurial and impulsive, and was frustrated that “the president struggled to focus during meandering conversations”. Trump dismissed Tillerson and called him ‘dumb’.)

Putin can play with Trump and Trump will think he’s being tickled and would see only the amusement

- Kenneth Craddock

“Putin can play with Trump and Trump will think he’s being tickled and would see only the amusement”, says Craddock.

A return to 1787: the lesson Journalism must learn on how to report on presidential candidates

Craddock warns that ‘performers’ like Trump will get through unless journalists change the focus of their questions from ‘horizontal’ to ‘vertical’, and begin to home in on the form of the candidate’s thinking, not merely the content – their political positions.

“Craddock warns that ‘performers’ like Trump will get through unless journalists change the focus of their questions from ‘horizontal’ to ‘vertical’”

“The media is asking the wrong questions, the horizontal ones” currently, he laments – it focuses on the content rather than the form of politics, probing for policies on issues rather than uncovering candidates’ ability to do the job.

Reversing this would mark “a return to the vertical view that existed in 1787”[when the US Constitution was drafted], says Craddock.

“The founders assumed the voters could see and hear the cognitive differences between the candidates to determine which of them was cognitively able to do the job… as they themselves did”

- Kenneth Craddock

“The founders assumed the voters could see and hear the cognitive differences between the candidates to determine which of them was cognitively able to do the job. They assumed the voters viewed the candidates vertically as they themselves did”.

In recent times, voting is itself even shifting away from any focus on personal attributes towards partisan ideology. (Some even fear that populism has revealed some deep weaknesses within democracy itself (see for example Prof Shawn Rosenberg’s Democracy Devouring Itself – the Rise of the Incompetent Citizen and the Appeal of Right wing Populism. Rosenberg even explicitly suggests in his article Unfit for Democracy? Irrational, Rationalizing, and Biologically Predisposed Citizens that citizen education will need to be rethought to enable the same kind of maturational shift towards transformative/architect thinking/’higher-order cognition’ that I’ve previously discussed).

It’s hard – but not impossible – to imagine the media at least sometimes trying to probe the ‘vertical’ competency of Presidents, rather than the ‘horizontal’ issues of specific policy content etc. (And – as for the UK – we don’t yet have anything like Craddock’s book, Brause’s PhD or similar blogs that analyse out political candidates’ complexity and competency. This offers a great opportunity for a researcher here in the UK to make a name for themselves by being the first to study this important and revealing topic, that might help improve our democracy and even our whole society!).

Can we believe this evidence?

These conclusions about presidential cognitive capabilities are not – or at least shouldn’t be – just people’s subjective (hence at times political) judgements on Trump and others, but are rather the results of neutral analysis, using apolitical methods that long-predate Trump’s emergence onto the political scene. And – as you’ve seen above – both Republicans and Democrats sometimes come out as higher level, longer time-horizon leaders, or often fail to reach the desired threshold of competence (eg the whole of this century so far!).

But I can’t from my own experience vouch for the accuracy of these Presidential levels found in debates – and the book itself doesn’t include the detail of how exactly the assessment of levels was done (eg debate snippets and their logics). Alison Brause’s PhD does however lend further credence to this particular method for analysis of presidential debates.

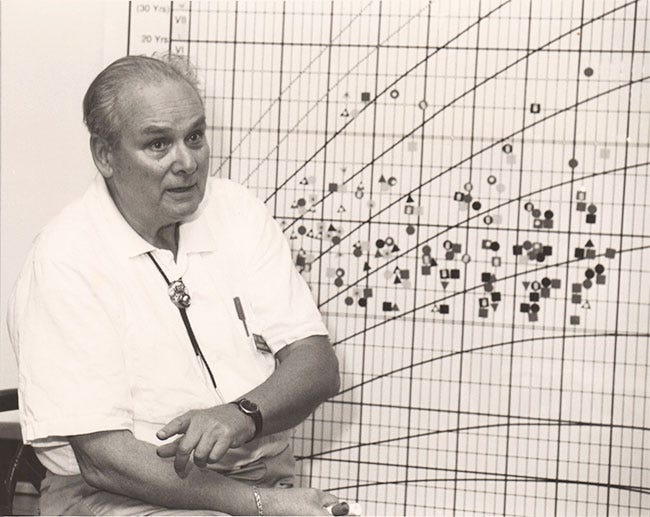

And it’s worth realising too that Dr. Elliot Jaques’ ‘Requisite’ model, that Craddock bases his analysis on, has been in use for 70 years or so. It’s hardly some implausible and out-on-a-limb approach either: models and research developed independently – eg by Prof Kurt Fischer, Prof Michael Commons and Dr. Theo Dawson, reaches strikingly similar conclusions about how cognitive capability grows in adults.

A book Jaques co-authored – Human Capability – a study of individual potential and its application – is also there for anyone who wants to probe more deeply into this method, and includes some snippets of ‘illustrative case material’ in an appendix, annotated with the logical chains and links they include and the overall logic chosen as a result.

If I didn’t already know how, well…, peeved he’d probably be at the potential conclusions from this article, I’d be tempted to ask my childhood London opposite neighbour Sebastian Gorka whether this analysis of Trump is hitting the mark, based on his experience of being a deputy assistant to President Trump, during his first Presidency, and potentially his second too. (His parents, like my father, were Hungarian – and became family friends). Oddly enough – as if to somehow balance things out politically – a renowned leftwing feminist, Ann Oakley, author of The Men’s Room and The Sociology of Housework and daughter of Prof Richard Titmuss, lived only a few doors down from the Gorkas. (That is, before she departed for more elevated intellectual climes in North London).

Some further validation is found in the research of Dr. Theo Dawson, in blogs she shared from 2017 to 2020. She concludes (see blog here) – via use of her own automated cognitive complexity assessment – that President Trump far from being the ‘evil genius’ some believe him to be, in reality has low complexity scores, which – she argues – suggest the following characteristics about him:

President Trump would view complex issues in simplistic, black and white, either-or terms.

He would not be able to incorporate the consideration of long-term implications in his decisions.

He would not be able to take into account the perspectives of more than one or two stakeholders at a time.

And he would not be able to see the complexity inherent in many of the issues he would face as president.

Consequently, he would be entirely incapable of formulating or recognising an optimal solution to a highly complex problem.

It’s interesting to note that Dawson’s team had been asked on several occasions in recent decades to evaluate the complexity of national leaders’ reasoning skills. They wouldn’t do it until it could be scored automatically, without the risk of human (political) bias.

Wouldn’t it be rather fabulous if one day we could all get to hear Craddock, Dawson and Brause in discussion, about the cognitive complexity of presidents and presidential candidates? And about the issue of how we might all in future help ensure that competent Presidents – and Prime Ministers, Chancellors etc of course too – are more likely to be recognised and chosen.

And we should also invite along someone like Harold Robertson (the author of the article ‘Complex Systems Won’t Survive the Competence Crisis’) too, as that triumvirate will need to be able to show that the ‘Archimedes Principle’ can stand up strongly against the explanation seemingly favoured by Trump: that recruitment driven by DEI goals is the key source of leadership incompetence in organisations. (NB I don’t know if Harold Robertson is himself a Trump supporter or not – his article was written for a San Francisco-based ‘non-partisan’ magazine on the future of governance and society).

Trump will get quite a shock if he realises that he himself could be the bigger peril facing complex systems, not DEI recruitment. Though – obviously – if there are instances where a less competent leader (eg lower level, lacking dynamic logic, short time-horizon) is recruited largely due to having desired DEI characteristics, that leader could well activate the ‘Archimedes Principle’ and shrink their organisation and its overall competence and capability. I suspect this is rare, though this kind of thing is clearly possible: in a similar vein, the US Supreme Court, for example, ruled in 2023 that Harvard University must cease to continue quietly using race-conscious admissions policies (ie significantly higher entry requirements for Asian applicants in order to reduce their overall proportion in the study body).

The argument being made in this post would also be weakened, I suspect, if we end up laying rather too much at the door of Trump himself, which I think Craddock may be at risk of doing, at times. For example, he writes: “Anarchy has spread beyond Trump’s control. Mobs are breaking into stores countrywide and looting the merchandise”.

They “clean out everything in the store”, he says.

“Several chains closed stores due to huge losses in these stories due to robberies”.

By contrast, “Biden is not advocating mobs or anarchy”, Craddock says.

Yet Democrats do seem to have more than done their bit to accelerate a noticeable increase in crime, a sense of lawlessness, and decline in quality of life, in some cities they run. It seems to be some progressive Democrat-backed policies such as decriminalisation of drugs, reduced penalties for shoplifting (if the value is under $950) and suchlike that appear to have – inadvertently? – opened the door to the shoplifting epidemic that Craddock decries. This problem is widely enough felt to be real by voters that there have been successful recall votes against prominent ‘soft on crime’ Democrat figures like Chesa Boudin (San Francisco District Attorney) and Sheng Tao (Mayor of Oakland).

How much blame can be put on Trump for this?

Of course, there are arguably more than enough red flags around Trump, which do appear to be true. For example, he’s apparently always shunned accountability, not allowing any note-taking in his presence – thus enabling total deniability. Mafia bosses use this same technique, says Craddock.

How can turn an ‘Archimedes Principle’ organisational decline into growth: from creating more headroom to raise the organisational ceiling, to a full organisational redesign

To ensure your organisation doesn’t fall victim to a leader who activates a negative ‘Archimedes Principle’ downward spiral that shrinks the organisations – lowering the ceiling of what’s possible – but instead grows it, the least we can do is ensure the top leader has additional ‘headroom’ to support that organisational growth.

In a previous post I explained how we can recruit transforming ‘Architect’ leaders – leaders with more headroom who work better with complexity, and use longer time-horizons – by using a leadership maturity assessment. This is a very low-cost – but potentially high-impact – intervention (see the Kent County Council/Swindon Council example I shared).

As mentioned before, proliferating the ‘Architect’ leaders, in the NHS and elsewhere, could grow effectiveness by 10% across a sector, the evidences suggests. I also show how we can study whether current leadership development programmes are successful at growing transformative ‘Architect’ leadership capacities, or are failing to – and identify which are the most valuable elements within leadership programmes that do support leadership growth.

A full ‘Requisite’ restructure to release organisational potential – through every level

Beyond just focusing on what a better top leader alone makes possible, a more comprehensive solution – optimising all the levels and roles across the whole organisation – requires a complete analysis of the organisation’s current structure and then a proposed restructure.

As mentioned, Craddock’s analysis of Presidents (and organisations) builds on 70 or so years of solid ‘Requisite organisation’ research and practice on structuring and designing organisations so that they fit best around how individuals develop psychologically, growing in capability and time-horizons.

This research was led by Dr Elliott Jaques and others, and is known by a number of labels: Requisite Organisation, Stratified Systems Theory, Levels of Work etc.

A ‘Requisite’ structure is an organisational hierarchy that has the right number of layers for the complexity of the work (and then people with the right capability or leadership Level – ie cognitive complexity/time horizons – chosen to fill all the roles in this structure). Each such layer adds unique value. There won’t be over-large gaps between layers, meaning staff lose direction – or bunching of layers, crowding of roles etc, which stops people working to their full potential.

Each leadership level – and the lower levels too – (ie 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 etc as needed) should have one organisational layer. As the then Principal Private Secretary at the Department of Health Clare Moriarty has pointed out in her 2009 internal Dept. of Health proposal for a ‘Requisite’ restructure of the whole NHS, historical analysis of the NHS shows that NHS configurations that break this rule all tend to be dysfunctional.

Too many layers means that they all lack headroom, have a sense of crowding and can fail to add value; responsibilities get split between layers or duplicated. The overview gained from being a level up is lost, meaning one management layer cannot give context to the one below.

The nesting of layers with increasing time-horizons and the right people in these roles means there’s a more realistic chance that long-term strategies will be successfully realised.

The NHS was itself actually, for a decade or two, a particular focus for such ‘Requisite’ analysis and practice (led by a research centre at Brunel University).

What might a ‘Requisite’ structure look like in the NHS?

The current underlying organisational design of the NHS is likely often to be far from ‘Requisite’. This means there are many prevalent dysfunctions in the organisational structure, which prevent effective work, drive up costs significantly, lower productivity and generally stymie the realisation of people’s full potential at work. And also limit an organisation’s capacity to work effectively over longer-term time horizons (eg 5 years, 10 years, 20+ years) and more.

These dysfunctions include things like:

Organisational layers too compressed together, with crowding of roles (which happens 36% of the time according to Capelle Associates), or with too much of gap between them (9% of the time)

Capability mismatched to role – meaning people are consistently either under-used or ‘in over their heads’ in their work (happens with around 35% of staff).

Manager alignment to their direct reports is wrong around 50% of the time. (For example, a manager with too low a level of capability compared to their subordinate will destroy creativity and innovation).

Studies have shown that only around 25% of senior staff are free of these issues and able to work effectively – meaning there is currently a huge amount of waste and unnecessary cost.

In a non-requisite structure, high-potential individuals – who do more than is required – will often be seen as a threat, held back or disparaged by their manager.

With so many people seemingly so blatantly misaligned in their organisations, it’s little wonder we see such widespread organisational dysfunction in our workplaces – though the actual causes of these problems, rooted in a sub-optimal non-requisite organisational structure – are usually overlooked, and people instead – wrongly – prefer to blame the visible symptoms they see on issues of low trust, poor communication, personality clashes and suchlike.

The following comment from Bioss* gives an idea of what improvements a ‘Requisite’ structure might bring to the NHS:

“Looking through the lens of Bioss* models, the NHS can be seen as a complex organisation trying to meet increasing demand with limited resources. In similarly complex groups, we see evidence of decisions either being taken, or being avoided, by people whose capability to engage with complexity does not match the challenge of the tasks that they face i.e. they are out of flow with their work. This can be costly and inefficient.”

“Although we have no available data on today’s circumstances in the NHS management structures, our research in another complex group found that among 460 middle and senior executives, only 25% were seen as being ‘In Flow’, 65% were in ‘Disuse’ (i.e. under-used, with capability not used in their work) and 10% were thought to be in ‘Mis-use’ (i.e. not yet capable of engaging with the complexity in their work.)”

“Similarly, in another large organisation we found that the consequence of senior leaders being out of flow was that costs rose and waste increased. A conservative estimate was that 20% of senior leaders were out of flow. On a salary bill of €500 million this meant that cost of underutilisation was €100 million, and that was without the duplication that will occur in these situations.”

(*Bioss is the Requisite-oriented consultancy organisation, originally based at Brunel University, that has worked with the NHS and other organisations.)

Clare Moriarty’s 2009 proposal for the NHS to move to a ‘Requisite’ structure mentioned how the shift from operational effectiveness to strategic vision (Level 3 to Level 4) has proven particularly problematic for the NHS. The objective of many NHS initiatives is that particular shift, though it’s not stated in those terms.

Elements of the Level 4 (strategic vision) function have often been assigned to various organisations leaving none of them with a clear and coherent role at a single level. The NHS regional tier has historically been particularly problematic in relation to some of these issues too.

Productivity in the NHS

Currently it appears to be things like AI and the return of hospital league tables that get proposed as the panaceas for apparent problems such as the current low productivity in the NHS.

What if it’s actually not these fixes but removing all the commonly-found dysfunctions of a non-Requisite structure that is what would truly unlock productivity gains in the NHS in the long-term, and let it reach its potential? This approach also produces much clearer accountabilities, something that is prominently called for in the recent Darzi report into the NHS.

There’s certainly a fair amount of evidence about the positive effects of implementing ‘Requisite’ structures on productivity. It has been used in hospital systems, the NHS and numerous commercial organisations. (And even a seemingly unrelated approach – The Leadership Pipeline model (that was popularised in a best-selling book) – has its foundation in the ‘Requisite’ Levels of Work approach). The productivity increases that typically follow, in commercial organisations, give rise to significantly increased quality and profits.

For example, a Levels of Work/Requisite analysis of the Royal Ottawa Health Group hospital system found numerous issues including most employees working at too low a level, along with inconsistent layers, unreasonable spans of control, financial issues, high staff turnover etc. A ‘Requisite’ restructure led to significant improvements in workplace satisfaction, financial performance and more.

The US Army Medical Department and other organisations saw productivity increases of around 30% after their ‘Requisite’ restructures.

In the commercial world, a declining white goods manufacturer was transformed into becoming the number one in the country, with 33% higher sales over a year, plus quality improvements and higher morale.

“We began to see previously stifled managers highly energised and dealing with business issues head on, and very effectively”

And here’s another example (from Canadian Tire Acceptance Ltd): “Within 9 months of initiating [Requisite] structure and people changes, we began to see previously stifled managers highly energised and dealing with business issues head on, and very effectively”, along with huge increases in revenue and becoming recognised as a ‘Top 100’ company to work for.

A metals company saw dramatic improvement in productivity and in customer relationships, plus a 50% increase in production. The previously poor relationship with the trade union was transformed.

Overall, 20% to 40% increases in productivity are apparently common, when the transformation to a ‘Requisite’ structure is made. (Let me know if you’ve heard otherwise!).

If NHS productivity is such a problem, shouldn’t we test wat effect some ‘Requisite’ restructures have? (In a similar vein to the five trusts that tried out the ‘Lean’ improvement approach from the Virginia Mason Institute from the US).

The traditional hierarchy vs flatter structure conundrum

All this discussion of the optimisation of organisational hierarches could make it seems like we’re ignoring the fabulous recent successes of autonomous teams, self-managed organisations and so on (I gave an overview of their highly promising – yet often stymied – impact in UK healthcare here).

But what if there isn’t quite the chasm we might imagine between the hierarchical and non–hierarchical approaches to organisations?

For example, the book that has done more than any other to popularise and fuel the recent surge in popularity of self-managed and flatter organisational structures (like Buurtzorg neighbourhood care) – Frederic Laloux’s Reinventing Organizations – downplayed or over-looked the key role of an ‘Architect’-style leader in holding the space for successful self-management, as Laloux himself later realised.

Self-management champion and trainer Lisa Gill recently concluded from her decade of experience working in that space that: “It’s impossible to eliminate hierarchy – trying to do so produces ‘leadership by stealth’” (see her Linkedin post).

“It’s impossible to eliminate hierarchy – trying to do so produces ‘leadership by stealth’”

- Lisa Gill

“What’s more fruitful is to aim for dynamic, chosen hierarchies and to be willing to be open about power dynamics rather than pretend they are not there”, she says.

Key is to “allow for natural leadership to flourish and flow to where it’s needed – for people to be able to step in and out as needed”.

So “bossless does not mean leaderless, but leaderful”, she concluded.

“bossless does not mean leaderless, but leaderful”

- Lisa Gill

All this certainly seems to suggest that there isn’t ultimately quite the stark chasm most – including me, I think! – imagine there is between the hierarchical models of organisations and the non-hierarchical ones.

Maybe a conversation between a Requisite hierarchy expert like Ken Craddock (or Gillian Stamp) and some self-management proponents like Laloux, Gill or Asst. Prof. Michael Y. Lee (and others like Prof. Bill Torbert who would understand and honour the different camps) could come up with a powerful rapprochement, with plenty of areas of agreement? And the ‘Holacracy’ approach to self-management actually already draws on Requisite (in a way I’ve yet to really understand), so its developer Brian Robertson would be particularly relevant to involve in any such conversation/inquiry).

I’d love to see what insights about all organisations might emerge from such a conversation across the hierarchy and non-hierarchy polarity.

In the interest of brevity – don’t laugh! – I won’t also ruminate here on how to remove ‘Failure Demand’ from your organisation. For inspiration, look at the current practices around ‘Liberated (Public) Services’, eg on the Human Learning Systems website (with all its great case studies); Demos’ recent reports and John Seddon’s books, for instance.

Some of these sources focus on Failure Demand much more than others, Seddon for instance. Demos, by contrast, rather downplays it (and, perhaps by focusing more on the new structures needed, also has said little so far about the kind of ‘Architect’-style leadership that may well be needed if Liberated Services are to thrive, or – relatedly – how the leadership ‘Archimedes Principle’ can grow or shrink an organisation’s capabilities).

Something to learn from Toyota’s Hoshin Kanri strategy?

As well as his deep interest and involvement in leadership capability and Jaques’ ‘Requisite’ structures that aim to help people fulfil their potential, Craddock is also very interested in the discipline of Quality Improvement, which has been embraced by the Japanese particularly wholeheartedly. (At Columbia Business School, he was the teaching assistant to W. Edwards Deming, possibly the biggest name in Quality Improvement).

Ironically, the Japanese proved far more receptive to Deming’s message on how to increase Quality (and reduce Failure Demand), on his visits from the US, than his home-country was.

“Toyota, like many Japanese firms,… vertically combined Deming’s improvement cycle and Jaques’ time-spans to ensure objectives were attained ahead of the competition… The impact crushed the three Detroit-based automakers in 2006”

- Ken Craddock

In his chapter in the book, Organization Design, Levels of Work and Human Capability, Craddock shared how “Toyota, like many Japanese firms,… vertically combined Deming’s improvement cycle and Jaques’ time-spans to ensure objectives were attained ahead of the competition… The impact crushed the three Detroit-based automakers in 2006”.

This mix of Requisite hierarchical decision-making combined with Deming’s statistical quality improvement went unnoticed by the Americans – “the impact of this combination was enormous. Immediately the increase in Japanese gross national product shot up to near ten percent per year”, writes Craddock.

“The impact of this combination was enormous. Immediately the increase in Japanese gross national product shot up to near ten percent per year”

- Ken Craddock

This seemingly hugely impactful approach to organsational strategy is called hoshin kanri, Craddock explains.

The question arises: could hoshin kanri have a positive impact in countries outside the Japan, were it to become more prevalent?

Craddock warns that US organisations will continue to be out-performed by organisations elsewhere that have had hoshin kanri installed.

Interestingly, the ‘Requisite’ approach Craddock recommends can even be used to ascertain the overall level of an organisation’s Quality function and then to decide whether a full Toyota-style level-shifting strategy is needed, or not. (It would surely be very illuminating to see the results of such an analysis of the current level of the NHS’ Quality function, and very timely too, with an NHS Quality strategy now under development).

Craddock shares that both the statistical techniques for improving quality (ie statistical quality control), as well as ‘Requisite’ organisation concepts around natural hierarchy are taught in high schools in Japan and other countries. He even adds that non-linear system change is also apparently taught universally in Japan. I feel like I need to hear more about all this to really believe it – but teaching foundational statistical techniques for understanding how to improve quality does feel like something the Government’s current curriculum review ought perhaps to consider, if it works in Japan (I think this is what the NHS’ Making Data Count/Plot the Dots training currently does rather fabulously). Ditto non-linear system change.

The US’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) – is it turning out to be a downward ‘Archimedes Principle’ spiral?

I’ve talked above about how to grow a sector’s effectiveness by 10% through the simple-ish step of recruiting more ‘Architect’ leaders. Also potentially saving tens of billions by spreading the inspiring ‘Liberated Public Services’ that treat people as real individuals and so cut Failure Demand. And the big increases in productivity and effectiveness when a ‘Requisite’ restructure is put in place. I even mentioned a 10% increase in GDP. Of course I don’t expect things to pan out just like this, but this does suggest the big possibilities in these areas.

Rather ironically, these solutions for more effective, productive, inexpensive public services are the kind of thing Elon could choose to be doing with his DOGE. Yet what he seems rather to be doing instead is a short-term mix of slash-and-burn job cuts and political purges. At one point recently, 300 of the vital staff that oversee the US’s nuclear weapons were even fired (AP News reports) – before Trump’s administration realised what they were responsible for.

A third of the US Digital Service recently quit after intrusive DOGE visits, AP reports, stating in their joint resignation letter that: “We will not use our skills as technologists to compromise core government systems, jeopardize Americans’ sensitive data, or dismantle critical public services.”

All of them had previously held senior roles in companies like Google and Amazon, and later joined US Digital Service out of a sense of duty to public service.

“These highly skilled civil servants were working to modernize Social Security, veterans’ services, tax filing, health care, disaster relief, student aid, and other critical services,” the resignation letter states.

The sudden loss of their technology expertise makes critical systems and American’s data less safe”

“Their removal endangers millions of Americans who rely on these services every day. The sudden loss of their technology expertise makes critical systems and American’s data less safe.”

The methods being used by DOGE hardly provide reassurance about when DOGE visits your organisation: “Several of these interviewers refused to identify themselves, asked questions about political loyalty, attempted to pit colleagues against each other, and demonstrated limited technical ability,” the US Digital Agency staff wrote in their resignation letter.

“This process created significant security risks.”

Like the nuclear staff, this is just one example – arguably – of the impact in a single department of the leadership ‘Archimedes Principle’: the crumbling of competence/capability and the shrinking of an organisation (the US Government) to fit the complexity/capability and time horizon of its new leader (President Trump).

As we saw Craddock warn: incompetent Presidents will appoint incompetent leaders further down the hierarchy (a ‘cascading effect’).

Let’s see what happens, over the coming months (or days!).

I personally find it hard to imagine that even Donald Trump’s worst fears about DEI would ever look quite like this level of damage from the ‘Archimedes Principle’ at work.

My own imaginary DOGE might instead build Liberated Services, dissolve Failure Demand, enable recruitment of far more collaborative ‘Architect’ leaders and support a mix of optimised ‘Requisite’ hierarchies and self-managed/autonomous team structures.

Elon could offer the needed training and support to any team in the public benefit sector. Unnecessary layers of management would be removed/reassigned and services become more effective and responsive.

This feels a whole lot more inspiring than Elon’s firings and political purges and would deliver growing benefits over many years (as the costs of strengths-based, community services like Buurtzorg – unusually – have been seen to reduce over time, perhaps because of the community assets activated, and prevention enabled).

Let’s hope ‘Liberated Services’ that treat people like humans again – rather than cogs or widgets – will soon become contagious and we’ll also be deliberately recruiting ‘Architect’ leaders who nourish the upward ‘Archimedes Principle’, not the downwards spirals.

NB If you want to try recruiting a more collaborative transforming/’Architect’ leader; or to try a fuller ‘Requisite’ restructure; or work to reduce ‘Failure Demand’ in your organisation but don’t know quite where to start yet, get in touch and I can pull together a list of organisations working to support people with these challenges.

Further reading - coming soon! (Please check back)

Quite a piece, Matthew! A few interesting new concepts for me in here.

I think we need to be cognisant of an organisations purpose (by which I mean the thing it is meant to be doing e.g. delivering health services, creating technology products, manufacturing cars etc) as this deternines what structures and concepts are appropriate. On organisation like the NHS has always been hierarchical and probably has to be, although there may be areas where a more self-organising approach can work. However, as we've seen, it's difficult to ringfence these and they tend to get neutralised by the organisational antibodies.

There are also certain beliefs and philosophies that underpin organisational strutures that need to be exposed and considered. Successful alternative to hierarchy, like Buurtzorg and Haier for example, have a depth and richness here that is lacking in traditional structures. The NHS also has this depth but it is only imprecisely articulated and often ignored, but it's why we are so proud of it as a symbol of our country.

I'll stop there before my comment get as long as your post!