Getting more participative ‘Architect’ leaders who can transform the NHS: what you said about them

A discussion of your feedback about participative 'Architect' leaders in the NHS - and next steps to help the NHS have conversations about them, and increase their number.

It was amazing to read all the spirited responses when I posted on Linkedin about my recent Substack article, ‘How the ‘biggest shift the NHS needs’ – more participative, architect-style leaders – can increase NHS performance by 10%’. (And to see that message get 10,000 impressions in just the first day or so after I posted it suggests it struck a chord for many).

“Interesting, challenging, necessary article” said one reader, Suzanne Steel, who also wondered “how we can be more Amar at a local level as leaders” (Some concrete suggestions on that follow further down). “Insightful and compelling” said Farhan Rafiq.

System change practitioner John Mortimer commented: “you truly looked at the whole systemic perspective (which I don’t think anyone else has done)”. “My mind is whirling on a Monday morning… thank you for a great read”, said Gina Sargeant.

It certainly feels like this vision Dr. Amar Shah shared – and I elaborated on – of a shift, of growing the number of participative and enabling ‘Architect’ leaders inside the NHS resonates for many people. Perhaps it was unsurprising that it sometimes seemed to fit straight into conversations people were already in the midst of: “Our conversation this morning”; “for our next chat”; “completely this”; “more of this” people said, often tagging in others.

How does the ‘Architect’ leader compare to other images of the future NHS that are on offer now?

In the news, there’s talk of a return to hospital league tables alongside a blunt ‘carrot and stick’ of punishments and financial rewards. Not exactly inspiring images for growing collective potential.

Evidence suggests distributed, collective, relational and system leadership is needed to bring about change in health systems

- Gerry McGivern

And the coming standardisation and regulation of NHS managers risks – says Gerry McGivern – resulting in “leaders and managers being more conservative and defensive, avoiding taking calculated risks or trying new things in challenging novel circumstances that would benefit patients or health systems.”

He also warns: “this approach focuses on individual leaders, when evidence suggests distributed, collective, relational and system leadership is needed to bring about change in health systems” – in other words, a far more ‘Architect’-style system-aware approach is what’s really needed now.

Can you envisage leader standardisation and regulation liberating the slightly maverick tendencies ‘Architects’ sometimes require, to make much-needed improvements?

Without a clear and inspiring purpose – such as growing, enabling or even just recruiting more ‘Architect’ leaders – we soon get into some real absurdities, I fear. For example, in my Substack post I mentioned Dr Bonnie Pierce’s findings amongst Nurse leaders, that many (and probably most) people struggle to publicly share bad news, to be candid about non-successes.

“Listening to discover how failures develop is an essential skill”, explains Bonnie – but it’s not one that is yet cultivated under the prevalent achiever ethos of the ‘Surgeon’ and related leader types: ‘organisational silence is the norm’.

Health Secretary Wes Streeting now talks about barring anyone who silences whistle-blowers – but an NHS that puts lots of the rapid impact ‘Surgeon’ type leaders I discussed in my post [not actual surgeons!] at the centre of things and far fewer ‘Architects’ more at the margins will always be tough for whistle-blowers. It will not be a ‘listening culture’.

The quick-fix of punishment for those who impede whistle-blowing is ironically just the kind of showy ‘Surgeon’ move that may well do little to change the organisation at the deep level needed. That’s my fear anyway, looking in on the NHS from outside.

And it makes it appear almost like we’d somehow have to get rid of quite a chunk of NHS staff because of the current non-Architect non-listening culture that too often prevails – rather than try to gradually change the underlying foundations for the better (which I’ve shown one largely untried path towards).

In August, even Wes himself was accused of exactly the kind of behaviour he now seems to be saying should get people barred (‘Health secretary Wes Streeting accused of ignoring whistleblower who revealed nursing scandal’, The Independent). I think this is a sign that threats of barring people from employment are just not going to have the positive effect envisaged. Fear, blame and low Psychological Safety is the antithesis of a culture that surfaces important safety issues. Though from a simplistic target-driven ‘Surgeon’ point of view, the reduced reporting of safety issues that would likely follow might be (mis-)used as evidence of a reduction in actual safety issues, when it actually means the opposite of this, as Prof Amy Edmondson showed in her book The Fearless Organisation – creating Psychological Safety in the workplace for learning, innovation and growth. Better teams appear to make more safety mistakes, as they make it safe and easy to speak up.

As Bonnie advises, assessing the leadership maturity of executive leadership teams and Nurse leaders “should become a risk management strategy for health care organisations”. In other words, start to find more ‘Architect’ leaders, who “demonstrate a superior ability to listen and create a climate for hearing concerns of the nursing staff”, and avoid thoughtlessly just adding more of those who lack this ability, as is too often the norm now. (If you would like some pointers about the various providers of such leadership maturity assessments please message me).

That’s a longer-term ‘Architect’ approach the NHS should try imho, rather than finding an individual to blame for the system’s current failings, and barring them.

I’m sure many of you will have other great ideas for catalysing more ‘Architect’ NHS leadership, beyond the two I focused on (which were evaluating whether leadership trainings are actually growing ‘Architect’ capacities or not, and simply recruiting more ‘Architects’ – where needed – helped by a leadership maturity psychometric).

One small example of these many other potential Architect-friendly good ideas could be the training of staff in ‘Dialogic’ change methods, that has recently been done by the NHS South, Central and West Commissioning Support Unit. This is a far more engaging and transformative ‘Architect’-style approach to change than the top-down, expert-driven norm. ‘Dialogic Organisation Development’ is now used as the umbrella term for the range of specific approaches like Appreciative Inquiry, Liberating Structures, Open Space, Future Search, Art of Hosting etc that have emerged more recently. This contrasts with the long-established traditional ‘Diagnostic OD’, which focuses on analysis of gaps and deficits and then linear planning and control to roll-out a change. It’s typified by best practices, benchmarking, finding the ‘right answer’ etc. That Commissioning Support Unit now has 12 accredited ‘Dialogic OD’ Practitioners.

I will discuss a range of such helpful small stepping stones like this in the upcoming second part of my 2023 post about place-based autonomous teams/Buurtzorg-inspired community nurses. (I basically came to the conclusion after writing the first half – and after talking with people like Helen Sanderson, Brendan Martin, Edel Harris and Annie Francis – that fully realising autonomous/self-managed place-based team approaches within the current NHS and social care structures faces so very many obstacles that smaller intermediate steps – that at least move in the right direction – felt important to focus on too).

Contracting with your staff – so your ‘Architect’ behaviour won’t be misconstrued as ‘weird’ or ‘unhelpful’

Some responses to my ‘Architect’ leadership post included great advice for leaders trying to put their ‘Architect’ thinking into practice. You may have yourself seen a leader who seeks to create space for staff to find the answers to problem themselves, deliberately holding back from the usual advocacy of their own favoured solution. I certainly have.

Do some contracting with teams before trying to launch into shifting their way of being and relating, so everyone is clear how they can help the experiment by doing their part. Without this, colleagues can simply feel [‘Architect’ leaders] are suddenly being ‘weird’ and ‘unhelpful’.

- Jennifer Flint

But without clarity about why this unusual behaviour is happening, some staff (even including their leader peers too) will inevitably soon be asking them to be more forthcoming with their own views, their own preferred solutions. It’s what we’ve come to expect leaders should be doing.

Jennifer Flint shared this fabulous advice: “the bit that often gets missed by managers (I did it myself before I knew better) is to do some contracting with teams before trying to launch into shifting their way of being and relating, so everyone is clear why this is happening and how it will work and how they can help the experiment by doing their part. Without this, colleagues can simply feel they [ie the ‘Architect’ leaders] are suddenly being ‘weird’ and ‘unhelpful’”.

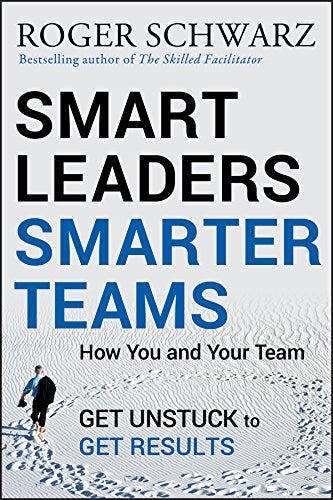

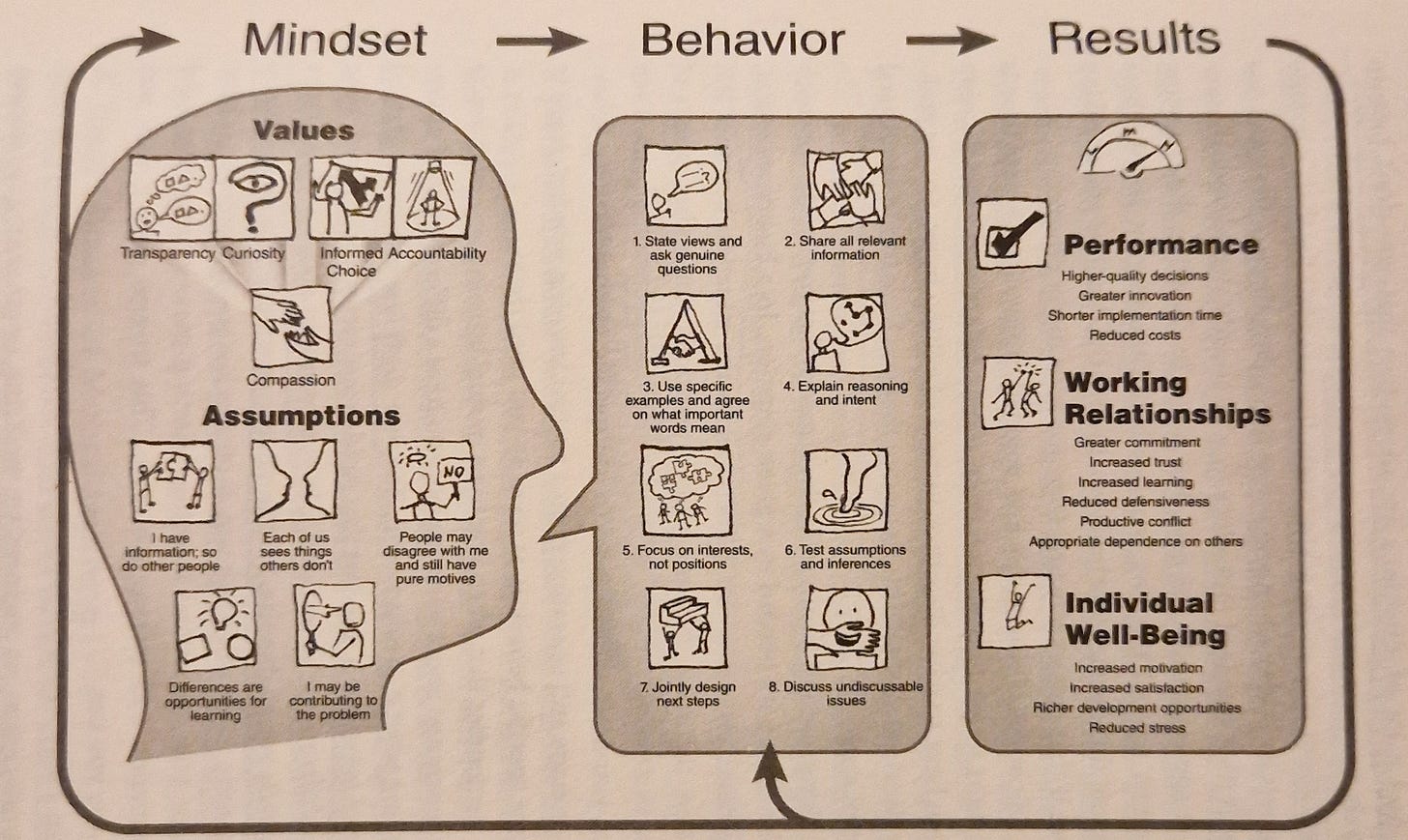

(The ‘Ground rules for effective groups’ shared near the start of The Skilled Facilitator Fieldbook, by Roger Schwarz et al, might be helpful for people wanting to undertake such contracting. And Schwarz’s ‘Skilled Facilitator’ method is itself, for me at least, one of the clearest approaches at explicitly moving behaviours in organisations away from an ethos of ‘unilateral control’ towards the Architect-friendly ethos of ‘mutual learning’, which is surely the real foundation for the continuous improvement Amar talks about).

Among all those thousands, we have identified fewer than 10 leaders who did not use the unilateral control approach

- Roger Schwarz

98% of leaders can’t be wrong? – oh yes they can be…

Schwarz also shares a sobering statistic about the real scale of the challenge in moving towards ‘Architect’ leadership in organisations like the NHS. Back in the 70s, renowned Organisation Development pioneers Profs. Chris Argyris and Don Schon did research that found that even in moderately challenging situations, 98% of professionals use a unilateral control mindset, despite its negative results. They studied 6,000 individuals. Since then, Schwarz and colleagues have themselves analysed thousands more.

“Among all those thousands, we have identified fewer than 10 leaders who did not use the unilateral control approach,” writes Schwarz in Smart Leaders, Smarter Teams (page 2).

Despite all the developments in leadership over the last forty years, when it comes to challenging situations almost all leaders slip into the same mindset

- Roger Schwarz

“Despite all the developments in leadership over the last forty years, when it comes to challenging situations almost all leaders slip into the same mindset”.

There – in a nutshell – is why the shift to participatory ‘Architect’ leadership is so hard to bring about in the NHS, and everywhere else. And why I think we need to assess leadership programmes in a new way and try something new with leader recruitment too.

There – in a nutshell – is why the shift to participatory ‘Architect’ leadership is so hard to bring about in the NHS

Without new actions like these, we may well be saying the same thing in another 40 years – wondering again why there’s been little sign of a deep shift in mindset and the enmeshed behaviours and structures.

This is also why psychological work to enable a deep – and enduring – change in mindset is necessary. No leader in unilateral control mode can work as an ‘Architect’ leader who empowers staff to solve the problems themselves.

(NB Healthcare does have its own unique problems too, of course. One rather unexpected one is that medical students are unique amongst all other students in actually going through moral regression as they progress through their Medical Education. This is thought to be influenced by the challenge of relating to clinical hierarchies and other things (see Hren). Perhaps the softened hierarchies built by participative, ‘Architect’ leaders will enable moral growth in some NHS staff too, as a by-product?).

Making the invisible visible: the ‘Left Hand Column Case’ exercise

To make things worse, the mindsets we use are – under normal circumstances – invisible to us. They are automatic and justified to ourselves without conscious thought. Most leaders these days learn to espouse collaboration, co-design et al whilst actually finding themselves doing the opposite – and also remain largely unaware that this is what they’re doing.

I’ve found that nearly all leaders who espouse mutual learning seem in fact to be operating from a unilateral control mindset. As a result, they undermine the very results they are trying to create

– Roger Schwarz

As Schwarz puts it: “I’ve found that nearly all leaders who espouse mutual learning seem in fact to be operating from a unilateral control mindset. As a result, they undermine the very results they are trying to create.”

To short-circuit our deep-seated habitual use of unilateral control/power, Prof. Argyris developed a practice called the ‘Left-Hand Column Case’ exercise to try to help us reveal our mindsets to ourselves. In this exercise one recalls an important but difficult conversation (even better if it’s a recurring one!). In the right-hand column you type exactly what was said. In the left-hand column you write down all the thoughts and feelings you had, whether or not you actually expressed them publicly. This should run to two or three pages. (I’ve slightly simplified, but this is the core of it). Through analysis, our mindsets actually in use and our espoused mindsets can begin to become visible and differentiated for us. The negative unintended consequences become easier to discern too.

The level of deep personal reflection that fosters facilitative leadership [such as ‘Architect’ leadership] does not occur until people examine how their mental models drive their behaviour

- The Skilled Facilitator Fieldbook

To re-iterate why such interior work is needed: “The level of deep personal reflection that fosters facilitative leadership [such as ‘Architect’ leadership] does not occur until people examine how their mental models drive their behaviour”, write Schwarz’s co-authors Anne Davidson and Dick McMahon, in The Skilled Facilitator Fieldbook.

As you can guess, though, with all the writing out of conversations and analysis, a Left Hand Column Case can be a somewhat laborious task. More recently the late Prof Argyris had also recommended Profs. Kegan/Lahey’s less time-consuming overcoming ‘Immunity to Change’ exercise as an alternative to Left-Hand Column Cases, that can similarly help grow self-awareness of our own mindsets at work, our unconscious processes.

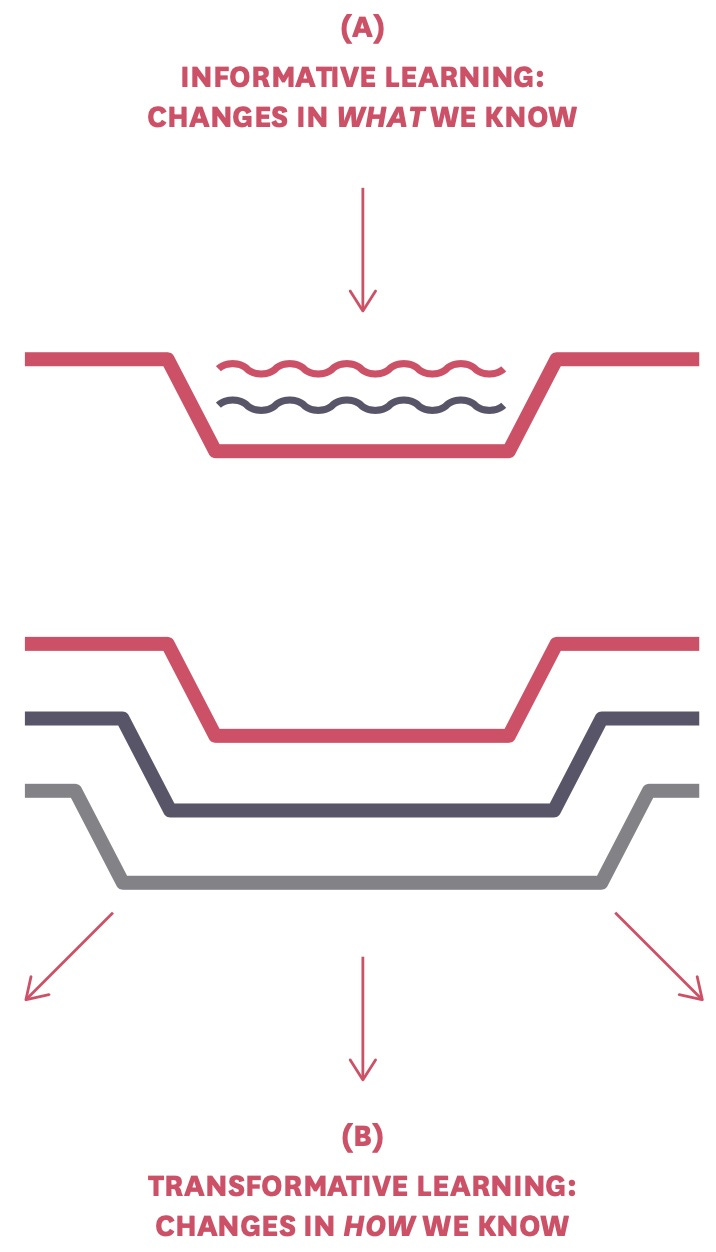

You may remember that this overcoming ‘Immunity to Change’ exercise came up a couple of times in my post, when organisations were trying to enable a shift towards ‘Architect’ style leadership in their leadership programmes. It’s far from the only tool at our disposal, of course – but the point is that we need to be using tools like this that help us make an inner change. The usual ‘informational learning’ mix of new skills, competencies and information isn’t enough: we need ‘transformational learning’ (more complex and sophisticated ways of thinking).

(For some pointers on what learning that is transformational – not merely informational – looks like: Manners, Durkin & Nesdale describe how such learning to enable inner shifts must be: “structurally disequilibrating, personally salient, emotionally engaging, and interpersonal.” Nick Petrie shows how ‘Heat Experiences,’ ‘Colliding Perspectives’, and ‘Elevated Sensemaking’ are needed for shifts. Boston & Ellis describe how to upgrade our perspective-shifting, self-relating, opposable thinking and sense-making. Drago-Severson offers four pillar practices: teaming, providing leadership roles, collegial inquiry and mentoring. Taylor, Marienau and Fiddler offer strategies and exercises with developmental intentions).

A reminder on unilateral control conversation vs mutual learning conversation and the sometimes fatal consequences

It’s easy to forget how seemingly minor differences between a prevalent ‘Surgeon’ conversational style – that’s more orientated towards unilateral control – and an ‘Architect’ style that’s more mutual – eg more likely to combine advocating with also checking about the other person’s response – can ultimately lead to huge differences in outcomes. And even fatal consequences.

The dominance of unilateral conversation – in medical situations – was illustrated in a simulated operating room study by Jenny Rudolph, as part of a training in avoiding errors for student physicians. The study found that of the total of 4,000 comments made by the lead physician during a simulated surgical crisis, only three comments combined unilateral advocacy with any checking into what their assistant was seeing or learning. This was despite half the group having been taught a method for inquiring in the midst of action just minutes before.

This ‘Surgeon’ ethos towards control, rather than collaborative learning, seemingly runs so deep: the student physicians’ “much more deeply internalised need to appear independent, competent and knowledgeable interfered with showing the vulnerability necessary to learn the data that can prevent error (as a number of them acknowledged in post-scenario interviews)”, Torbert and associates write in the book Action Inquiry: the secret of timely and transforming leadership.

In a similar vein, Prof Amy Edmondson’s research on ‘Speaking Up in the Operating Room’ – when a new surgical procedure requiring real interdisciplinary teamwork was introduced - describes how easily a surgical leader can signal to others that openness and mutual learning is okay, by highlighting the need for teamwork, stressing their own fallibility, limits and humility, by not over-reacting to mistakes etc.

But other surgeons would instead signal that this was business as usual with their own role in mastering the change still the key one. Their message was that rather than being “outgoing and in frequent contact with others” they desired that team members instead be “be inward looking with plans held closely”.

One Surgeon leader who was able to successfully move away from traditional ‘unilateral control’ towards team ‘mutual learning’ commented: “There is a whole new a wave of interaction... the ability of the surgeon to allow himself to become a partner not a dictator is critical. For example, you really have to change how you are doing something based on getting a suggestion from someone else on the team.”

The biggest air disaster in history – the 1977 Tenerife air crash, where two Boeing 747s collided killing 583 people – happened when hierarchical culture, deference to leaders and unilateral control conversations meant the crew didn’t strongly challenge the highly experienced captain’s decision to take off without clear permission.

This tragedy led to a cultural shift in aviation and the widespread adoption of ‘Crew Resource Management’ training that stressed open communication and shared decision-making regardless of rank – in other words a shift from the heroic ‘Surgeon’ leadership that airline captains had traditionally shown, towards a more participative ‘Architect’ leadership.

Hierarchy and the striving to be in unilateral control, rather than using mutual learning, were also factors that led to the 1986 space shuttle Challenger disaster too.

The battle to stop us automatically snapping back from ‘Architect’ leadership

So, mental espousals like ‘I support participation and Architect leadership’ won’t cut it, as we collapse back to ‘Surgeon’-like unilateral control under even mild workplace stress.

Regular use of self-awareness/change tools such as Immunity to Change, along with day-in, day-out use of team participatory practices such as Liberating Structures is the kind of thing that slowly builds a foundation for ‘Architect’ leadership that doesn’t melt away at the first sign of tension, snapping back to more ‘Surgeon’-like control. (NB Please don’t miss the free, or cut-price, places on Liberating Structures training workshops that Happy courses kindly offer to NHS staff and black-led organisations).

Don’t use ‘compassion’ as the excuse to protect your ‘undiscussables’

It's interesting that organisations so often choose to avoid discussing ‘undiscussable’ issues, seek to avoid any risk of making anyone feel embarrassed or defensive: “they see discussing undiscussable issues as not being compassionate. Yet people often overlook the negative systemic – and uncompassionate – consequences they create by not raising an undiscussable issue.” (The Skilled Facilitator Fieldbook, pg. 66).

I worry that otherwise very positive movements in healthcare – like Prof. Bob Klaber’s Kindness in healthcare movement and Prof. Michael West’s Compassionate Leadership – because they don’t discuss this prevalent dynamic (at least not that I’ve spotted yet) – risk inadvertently empowering the kind of defensive and over-protective ‘compassion’ that keeps crucial things undiscussable. This is the heart of what prevents the NHS ever becoming the ‘Learning Organisation’ it needs to become, I think.

Can organisations make vulnerability, learning and continuous improvement an everyday occurrence? The case of Deliberately Developmental Organisations/growth cultures.

At this point in writing this post I suddenly remembered a fabulous 2016 book by Profs Kegan, Lahey and colleagues called ‘An Everyone Culture – Becoming a deliberately developmental organisation’.

It describes in detail those – still few – organisations that banish the common charade of everyone pretending to be experts and instead make continuous learning the norm. Inadequacies and incompetencies are seen as a resource.

In contrast to most organisations, which have cultures designed for performance, these organisations’ cultures are designed for practice. They find numerous ways to help all staff live with the accompanying vulnerability of such daily learning and experiments.

The authors point out that most people today are currently spending time and energy on a ‘second job’ no-one is paying them for: “covering up their weaknesses, managing other people’s impressions of them, showing themselves to their best advantage, playing politics, hiding their inadequacies, hiding their uncertainties, hiding their limitations. Hiding”.

A safe yet demanding culture brings people out of hiding.

Organisations with ‘growth cultures’ value disturbance and give staff things like ‘plus-1 projects’, where they have to critique an accepted process and improve it. One of them created a ‘Pain Button’ App so people could easily record their negative emotions – to help people get ‘to the other side’, beyond their usual ego defences and able to discuss their limitations.

Another encourages all new staff to identify their ‘backhands’, their character weaknesses and less skilled areas. Everyone – from top leaders to newbies – is assumed to be working on their imbalance towards either ‘arrogance’ or towards ‘insecurity’, and to be ‘practicing their backhand’. And “everyone knows everyone else’s backhand, or, if they don’t, it is commonplace to inquire”.

All this practice means an improvement and growth in a person’s interior, not just in external work processes, as we usually see with Quality Improvement efforts in healthcare: “Unlike quality-improvement approaches such a Lean Six Sigma, a DDO’s [Deliberately Developmental Organisation’s] focus on processes is as likely to be about improving the quality of work done on members’ interiors (the development of individual psychological selves) and communities (how people relate to one another in collective responsibility) as it is on the external (such as measures of production-process errors and anomalies”.

These organisations also show that mutual learning and continuous improvement requires a very different type of organisation, where leaders no longer develop strategies for others, but become trustees for the principles of deliberate development and personal growth.

The three detailed case studies in that book are not healthcare systems, though a few healthcare organisations are now trying this approach.

How to get a rich discussion of ‘Architect’ leadership going in your own team

I do hope the inspiring image of the involving and enabling ‘Architect’ NHS leader – with their longer-term, more systemic eye – can help prompt wider discussion and then concrete changes too.

I am using [your post] as pre-reading for an NHS Trust site leadership team session next week

- Sarah Cowley

Along these lines, Sarah Cowley told me that ‘people are yearning for change’ and that the Substack post can help this to happen: “I am using it as pre-reading for an NHS Trust site leadership team session next week”.

Ways to discuss ‘Architect’ leadership with your team – and go deeper

An easy first step might be to simply discuss the barriers and enablers of ‘Architect’ leadership with your team, along with where it’s most needed, yet perhaps not yet seen (eg a complex problem that you’re struggling to make progress with).

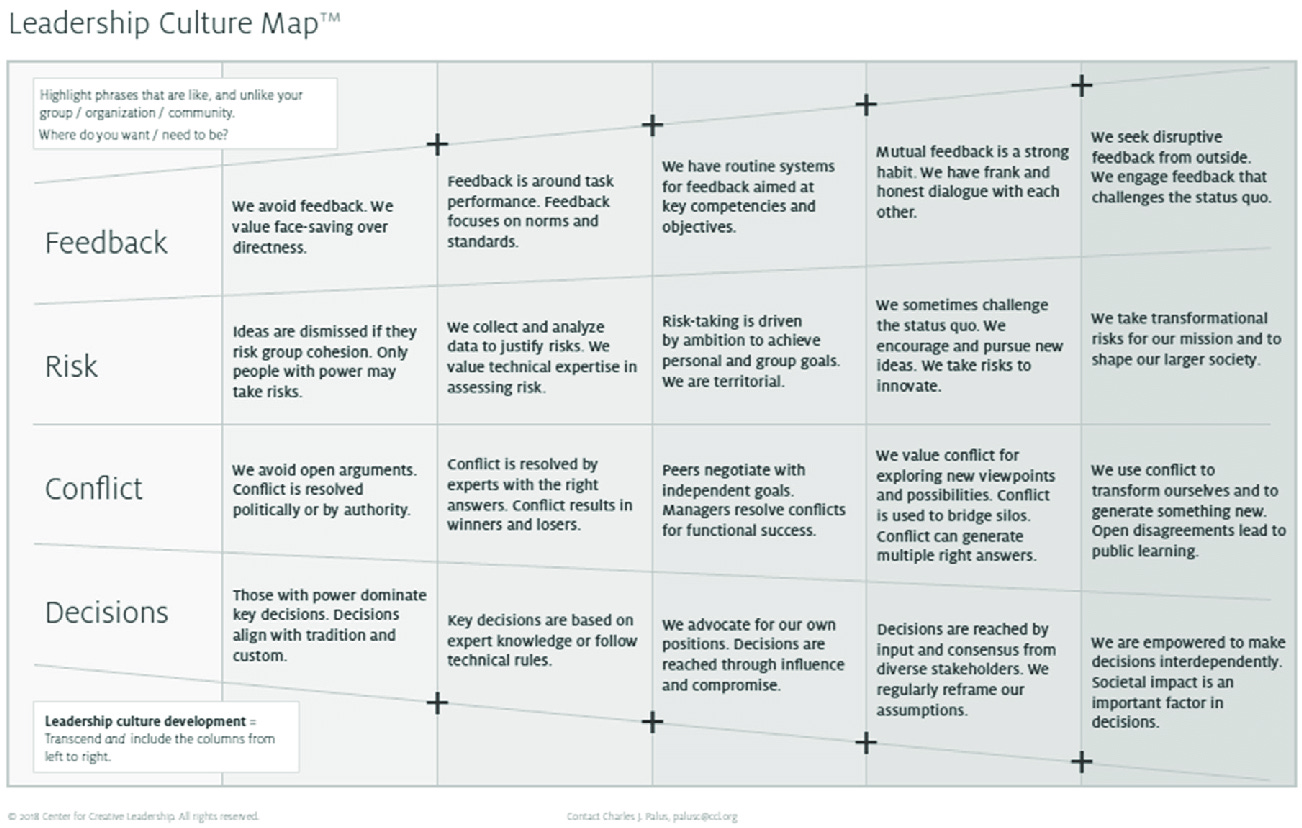

Beyond this, a more structured and comprehensive way to probe how ‘Architect’ leadership might positively impact different key facets of your organisation can be undertaken by making use of the “Leadership Culture Map’, developed by the respected Centre for Creative Leadership.

The rightmost two columns represent emerging ‘Architect’ leadership and full-blown ‘Architect’ leadership, respectively, I would suggest.

But where exactly is your organisation? Where are you as leaders?

To find out: in a team meeting give everyone red dots (to mark where they think the team is now) and green dots (for the desired future state). Another colour can be used to think about a point in each person’s past too, if desired.

Putting all these dots onto a poster-sized version of the ‘Leadership Culture Map’ opens up an opportunity for team discussion – about the tensions and possibilities that are made visible by the patterns of dots. Under what circumstances does ‘Architect’ behaviour become possible? You can come back a year later and do the same exercise – see if actions and experiments you agreed on have successfully enabled a cultural shift to the right, towards embedding ‘Architect’ leadership.

In a larger directorate there will likely be some micro-cultures that are already further to the right towards ‘Architect’ leadership. Learn from their ‘Architect’ behaviours and spread what works to other parts of the organisation. (Here’s a Liberating Structure called the ‘Discovery & Action Dialogue’ exercise to help you find your organisation’s ‘Positive Deviants’ , that might also help).

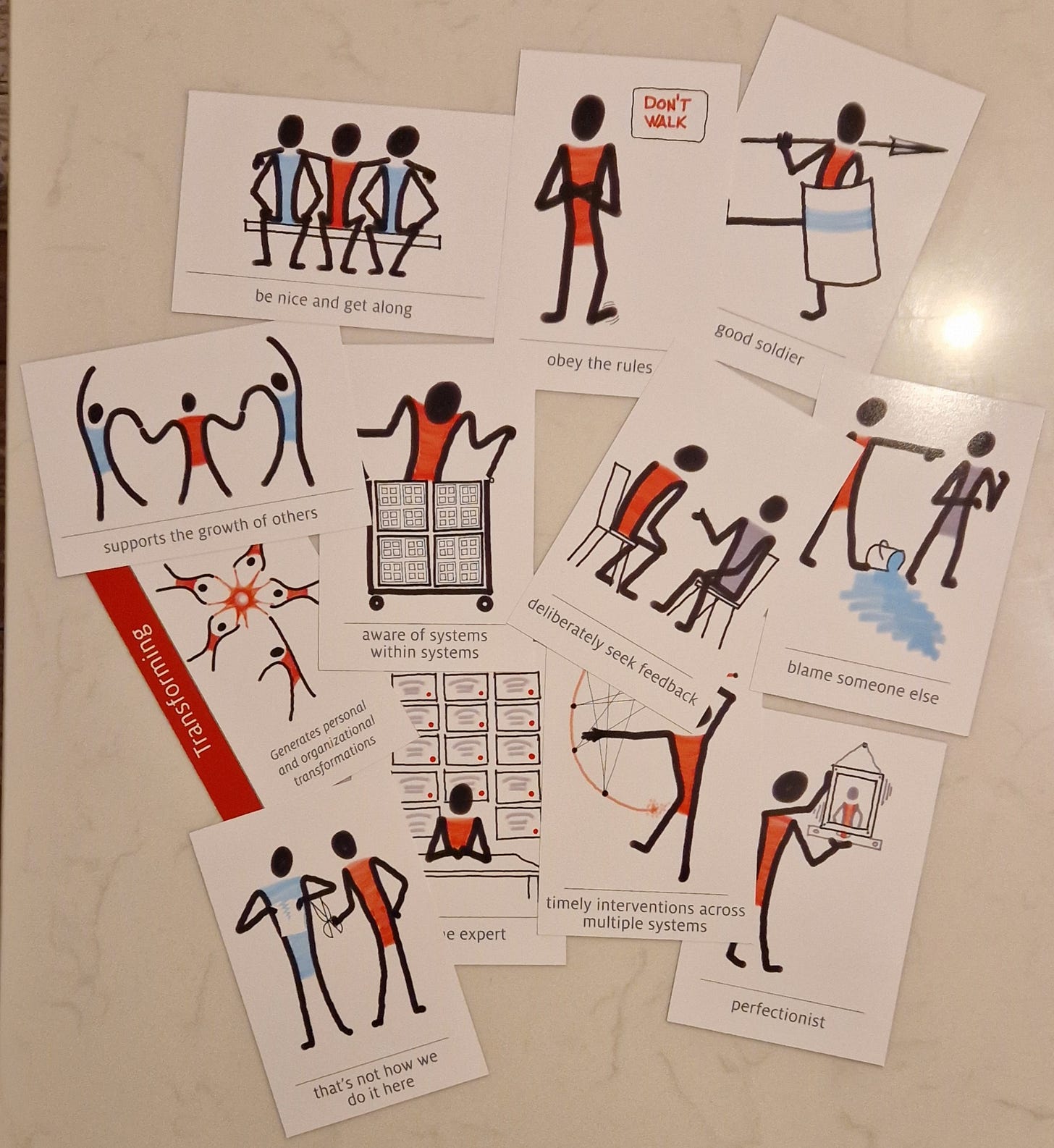

The Centre for Creative Leadership also have another helpful tool: sets of ‘Transformations’/‘Catalysts’ cards. These can be used for things like digging more deeply into a leadership team culture’s shift towards the ‘Architect’ mindset, and also to reflect on one’s own individual leadership journey and next steps. (I shared these cards with NHS change agent extraordinaire Helen Bevan, who – with her ‘NHS Horizons’ team – soon got hold of numerous packs and launched into using them with thousands of NHS staff and leaders).

Let’s not forget in all this, though, that there can be plenty of crucial participatory leadership activity that is often under the radar and outside the coterie of named ‘Leaders’. Read the book Systems Conveners – a crucial form of leadership for the 21st century (free PDF) for more on this. This short book is very much a guide to an ‘Architect’ form of leadership. But it’s the highly relational form of leadership where you don’t have positional authority to rely on, as conventional ‘System Leaders’ do. Find your organisation’s ‘Systems Conveners’ and you may find you already have quite a pool of ‘Architect’ leaders to draw on.

Before I wrap up this post, I did want to share that a few days ago I heard the Government’s Minister in charge of public sector reform, Georgia Gould MP, get strongly behind the ‘Liberated Services’ I mentioned later on in my post.

Deliberately recruiting an ‘Architect’ leader is what enabled a ‘Liberated’, relational approach to family support to be developed in Swindon

She was ‘blown away’ at the story of the millions spent by multiple services, including the NHS, on a single high-intensity user of services, Brian, as he got bounced between numerous siloed services – all of them failing to actually give him the help he needed to solve his underlying problem. Gateshead’s ‘Liberated Services’ approach made such a difference to his life that the local A&E presumed Brian had died once his regular appearances stopped when the relational ‘Liberated’ approach took over from the usual processes and silos on offer, said Georgia.

As described in my post, deliberately recruiting an ‘Architect’ leader is what enabled a ‘Liberated’, relational approach to family support to be developed in Swindon.

Imagine what could be achieved if we really got behind public service innovators

- Georgia Gould MP

“Imagine what could be achieved if we really got behind public service innovators”, like Gateshead’s ‘Liberated Services’, Georgia told the audience at a Demos event to launch their latest reports on reforms to bring in ‘Liberated Public Services’ around the UK.

Getting behind the innovators is why we need to be recruiting or developing far more ‘Architect’ leaders. It’s these ‘Architects’ who create the space for staff to innovate and solve the problems themselves, and are how we can ensure that more innovations will emerge and spread, I think. We just need the small thing of Central Government, the NHS Board et al to get behind this inspiring change, following Georgia Gould MP’s lead, both as the past leader of Camden Council and now as a Government Minister.

And perhaps ironic that someone once dismissively dubbed a New Labour ‘golden girl’ – on account of her New Labour grandee father, Philip Gould – may help precipitate a seismic shift beyond the ‘Markets, Managers and Measurement’ ethos of New Labour’s ‘New Public Management’ approach, back to something more human, community-based and effective. Maybe it somehow has to be this way for us all to believe it?

Further reading

Allen, Jane, Gutenkunst, Heidi and Torbert, William R (2018), Street Smart Awareness and Inquiry-in-Action (Amara Collaboration).

Argyris, Chris (1999), On Organizational Learning (Wiley, 2nd Edition).

Argyris, Chris (2018), Overcoming Organizational Defenses: Facilitating Organizational Learning (Pearson).

Boston, Richard and Ellis, Karen (2019), Upgrade – Building your capacity for complexity (LeaderSpace).

Bushe, Gervase (2020), The Dynamics of Generative Change (BMI Series in Dialogic OD).

Bushe, Gervase and Marshak, Robert (2015), Dialogic Organization Development: The Theory and Practice of Transformational Change (EDS Publications).

Curtis, Polly (December 2024), ‘Breaking central government’s grip’, Prospect.

Drago-Severson, Eleanor (2009), Leading Adult Learning: Supporting Adult Development in Our Schools (Corwin).

Edmondson, Amy (2003), ‘Speaking Up in the Operating Room: How Team Leaders Promote Learning in Interdisciplinary Action Teams’, Journal of Management Studies.

Edmondson, Amy (2018), The Fearless Organization - Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth (Wiley).

Fox, Alex and Fox, Chris (2024), The Motivational State - A strengths-based approach to improving public sector productivity (Demos).

Fox, Alex (2023), ‘Systems Convening – what you told us’ [blog].

Glover, Ben (2024), The Reform Dividend – a roadmap to liberate public services (Demos).

Glover, Ben (2024), Liberated Public Services: A new vision for citizens, professional and policy makers (Demos).

Hren D, Marušić M, Marušić A (2011), ‘Regression of Moral Reasoning during Medical Education: Combined Design Study to Evaluate the Effect of Clinical Study Years’, PLOS ONE.

Kegan, Robert and Lahey, Lisa Laskow (2009), Immunity to Change: How to Overcome It and Unlock the Potential in Yourself and Your Organization (Harvard Business Press).

Kegan, Robert, Lahey, Lisa et al. (2016), An Everyone Culture – Becoming a Deliberately Developmental Organization (Harvard Business Review Press).

Manners, John, Durkin, Kevin and Nesdale, Andrew (2004), ‘Promoting Advanced Ego Development Among Adults’, Journal of Adult Development.

McGivern, Gerry (Nov. 2024), ‘I'm not convinced that standardising and regulating NHS leaders and managers…’ [Linkedin post].

Mezey, Matthew (2023), ‘The possibility of autonomous Buurtzorg care teams across the UK: tantalising hope vs organisational rigidity (Part 1)’ [blog]

Petrie, Nick (n.d.), The How-To of Vertical Leadership Development – Part 2: 30 Experts, 3 Conditions, and 15 Approaches (Centre for Creative Leadership).

Pierce, Bonnie (2016), ‘Speaking Up: it requires leadership maturity’, Nurse Leader.

Schwarz, Roger et al (2005), The Skilled Facilitator Fieldbook: Tips, Tools, and Tested Methods for Consultants, Facilitators, Managers, Trainers, and Coaches (Jossey-Bass).

Schwarz, Roger et al (2013), Smart Leaders, Smarter Teams: How You and Your Team Get Unstuck to Get Results (Jossey-Bass).

Seddon, John et al (2014), Saving money by doing the right thing – why ‘local by default’ must replace ‘diseconomies of scale’ (Locality/Vanguard).

Taylor, Kathleen, Marienau, Catherine and Fiddler, Morris (2000), Developing Adult Learners – strategies for teachers and trainers (Jossey-Bass).

Thomas, Rebecca (August 2024), ‘Health secretary Wes Streeting accused of ignoring whistleblower who revealed nursing scandal’, The Independent.

Torbert, Bill and Associates (2004), Action Inquiry – The Secret of Timely and Transforming Leadership (Berrett-Koehler).

Voronov, Maxim and Yorks, Lyle (2015), ‘“Did You Notice That?” Theorizing Differences in the Capacity to Apprehend Institutional Contradictions’, Academy of Management Review.

Wenger-Trayner, Etienne and Wenger-Trayner, Beverley (2021), Systems Convening – a crucial form of leadership for the 21st century (Social Learning Lab). [free PDF]

Another great spot Matthew, thanks. You delve into the space that few dare to do - the depths of why real reform is so difficult. It does start with the mindset we hold.

But, one thing, I have found that indeed there are many managers that can shift this mindset. and we know how to do it. So the potential is there.